By Joshua Olson

Hi, I'm a borderline techno-utopian. At the moment I believe that in fifty years the world will be a more exciting place for me to participate in, and that's why I want to take my own nutrition seriously for purposes of longevity. If you want to keep up with the literature, you can't believe everything the FDA says; I have no clue how your country does it. Maybe it's better to turn to an exercise fitness magazine? A reputable online forum? Can YOU analyze the shortcomings of three related poorly reported double-blind studies with p-values and an uneasily broad or irrelevant-to-you demographic? Especially the studies behind science journal paywalls? Did Google ever mention genetics? Couldn't I find better sources than Wikipedia in my lazy incentive-driven human nature?

Whatever sources are accessible to you, either due to ignorance or your financial and sociopolitical situation, scientific principles are the key to effective engagement with information made available through mass media.

Common wisdom states that the internet is for porn. Next after that is political ignorance and trolling, terrorists and pirates, crackers and crackpots. But the human-readable information passing through the tubes of the internet itself is actually the World Wide Web, and that's where both the gold and turds of facts and fiction lay. Is this anything new? Is the digital age, or electronic age, or whatever internet age/generation we're called/in special?

Pfft, of course. Just like everyone and everything else in their little slice of history. And this applies to the accelerating structure of human understanding and misunderstanding we call the internet. But before it was accelerated, the recorded and therefore useful-to-the-masses science, journalism, and public political communication happened in letters, periodicals, books, and visual and performing art mediums.

Mass Media: Written Noise

For example, Hippocrates, practically the father of Western medicine and upon whom doctors often swear an oath at graduation if I'm informed, was one of the ancient perpetrators of the idea of the four humours: four types of fluid determine the balancing act that is health. By Shakespeare's day this wholly pseudoscientific system of justifications for blood letting and arbitrary dietary changes had expanded into the four temperments, stereotypes, cosmologies, and psychological personality classifications.

While this lack of critical thought may be justified by limited tools for measuring the human body, it wasn't dissection of animals that ended it, nor dissection of cadavers. No, it

- hasn't ended because the influence is still there in personality test voodoo, and

- the wide publication itself of more accurate explanations and data occured alongside the outdated theories, and only eventually did this have the desired impact.

The reader's experience on the

internet is indeed this very same simultaneity of garbage and

progressively less incorrect garbage. Such is the state of advancing

human knowledge in secular uncertainty and limited power to observe and

experiment with nature. That uncertainty which is inherent to our lives is precisely what the British philosopher John Locke meant by the provisionality of knowledge - judgment of reality is never finished. Heck, Plato asserted that deep conversations last a lifetime.

Dissection and Amateur Scientific Readers

In a collection of essays entitled Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow, Victoria Vesna points out that even with more information than we’ve ever had before, we still tend to view the world from a top-down perspective, which I define as drilling down from a common authority or concept of truth to a researcher-centric specialization despite data and ideas hanging around that don’t have a clear place or implication. Descartes’s reductionism and synthesis in the Enlightenment and the ancient rhetorical strategy of separating a topic into parts illustrates what we think of as analysis, which isn’t the whole story. Choosing where to find information and evaluate the likelihood of its accuracy cannot start with analysis but a vague but actionable/discussable theory - hypothesizing from, admittedly, person-centered beliefs and uneven prior exposure to ideas, experiences, and doubts. This is critical thinking, which is the first half of what science is all about (the second is doing, falsifying through action).

Vesna’s own specialization prevented her from realizing that ‘quantum leap’ is cliche and incorrect in almost any use. But in her non-literary and non-quantum profession, her view of dissection as evidence of Western medicine’s dehumanization has a connotation I disagree with and a denotation I wholeheartedly like. We absolutely have to separate facts from anecdotal stories to get anything done, whether we're researching political candidates, climate change, the best school or place to live, or even our own careers and charity efforts. I have a link for that last one, but have a bunch at the same time instead. Our lives are oriented in the information age around the vibrancy and overload of our new virtual connectedness. If your eyes are subjecting themselves to this exact text, you are already part of a tradition of critical thinking as old as text.

Who cares?

Consider a Latter-day Saint friend of mine, who argues that the biases in advertisements and popular cinema create and perpetuate some of the most egregious misrepresentations of information and religion in modernity. Better yet, consider an everyday university library help desk employee I interviewed. When asked how to determine the

dubiousness/truthfulness/accuracy of online information, she echoed

Descartes's method of verifying what you don't want to trust. I'll note that her suggestion of judging

people (ignoring anonymity) by their experience, position, who they

support, and who disagrees with them is similar to Google PageRank,

which judges reputability by link popularity, but recursively (gotta

know the relationships up to between specialized fields themselves). How

interesting.

I leave it as an exercise to the reader to understand how search engine use is therefore also ironic.

I leave it as an exercise to the reader to understand how search engine use is therefore also ironic.

Don't

be stupid. Everyone needs a lifetime to become 'well-informed/rounded'. Science is old. The internet isn't the only

place people talk and get things wrong, confusing, or misleading. It's sure been crucial to my search for good eating habits, however. Until I CAN judge p-values, part of my search involves an amateur expert community at http://diy.soylent.com/, where the nutritional values of combinations of foods and supplements are calculated and documented. Learning is a solo activity if you're ever going to take Descartes seriously, but find your best teachers anyway, and at least try to be aware of when one of them is no longer a decent source of gold nuggets among the turds.

Works Cited

1. The Hippocratic Corpus: An Ancient Library, the Four Humors, and Greek Orthopaedics. http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/antiqua/humoral/. University of Virginia. 2007.

2. The humours. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/ideas/order/humours.html. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 2011.

3. Black Bile and the other Humors. http://elsinore.ucsc.edu/melancholy/MelBile.html. Elsinore. 2001.

4. Four Humors. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/shakespeare/fourhumors.html. U.S. National Library of Medicine Exhibition Program. 2013.

5. Sadness and the four humours of Shakespeare. http://theshakespeareblog.com/2014/02/sadness-and-the-four-humours-in-shakespeare/. Sylvia Morris. 2014.

6. Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow. Book. Victoria Vesna. 2007.

7. Integration of Technology Disintegrates Religion. http://criticalcomms.blogspot.com/2016/06/the-integration-of-technology.html. Ryan Blaser. 2016.

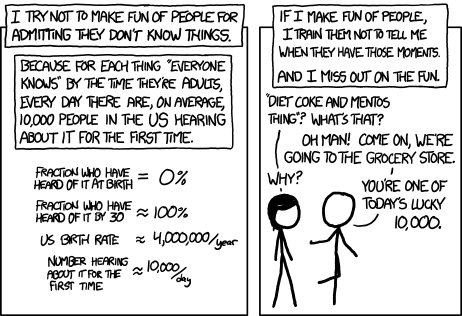

8. Ten Thousand. http://xkcd.com/1053/. Randall Munroe. 2012.

9. DIY Soylent. http://diy.soylent.com/. Website. 2016.

Works Cited

1. The Hippocratic Corpus: An Ancient Library, the Four Humors, and Greek Orthopaedics. http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/antiqua/humoral/. University of Virginia. 2007.

2. The humours. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/ideas/order/humours.html. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 2011.

3. Black Bile and the other Humors. http://elsinore.ucsc.edu/melancholy/MelBile.html. Elsinore. 2001.

4. Four Humors. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/shakespeare/fourhumors.html. U.S. National Library of Medicine Exhibition Program. 2013.

5. Sadness and the four humours of Shakespeare. http://theshakespeareblog.com/2014/02/sadness-and-the-four-humours-in-shakespeare/. Sylvia Morris. 2014.

6. Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow. Book. Victoria Vesna. 2007.

7. Integration of Technology Disintegrates Religion. http://criticalcomms.blogspot.com/2016/06/the-integration-of-technology.html. Ryan Blaser. 2016.

8. Ten Thousand. http://xkcd.com/1053/. Randall Munroe. 2012.

9. DIY Soylent. http://diy.soylent.com/. Website. 2016.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI can't fix the font size at the end.

ReplyDelete